A kiss to build a year on - if your brain's chemistry agrees

By Sheril Kirshenbaum

Thursday, December 23, 2010

Wednesday, December 29, 2010

Tuesday, December 28, 2010

Austerity: 2010's most searched for term

John Morse, president and publisher of the Springfield, Mass.-based dictionary, said "austerity" saw more than 250,000 searches on the dictionary's free online tool

Austerity, the 14th century noun defined as "the quality or state of being austere" and "enforced or extreme economy,"

Let's look at Webster's definition for austere:

aus·tere adj \ȯ-ˈstir also -ˈster\

Definition of AUSTERE

1a : stern and cold in appearance or manner b : somber, grave

2: morally strict : ascetic

3: markedly simple or unadorned

4: giving little or no scope for pleasure

5of a wine : having the flavor of acid or tannin predominant over fruit flavors usually indicating a capacity for aging

— aus·tere·ly adverb

— aus·tere·ness noun

Doesn't sound like much fun but is it such a bad thing?

Morally strict... who's morals? Pagan Morals? Would it be such a bad thing, if we were to have Pagan austerity? Where by we only used cloth shopping bags, paid more attention to shopping local whether that was local produced food or arts and crafts or services. If we worked to plant more trees to help with carbon capture? If we worked for bike paths and quality sidewalks that would encourage people to walk more than drive? If we did our best to live lightly on the earth and in the process we lived a simple life and enjoyed life's pleasures, love and each other and the glow of a fire or the warmth of a cup of tea or the way the moonlight can create a soft blue glow? Would that really be so bad?

Austerity, the 14th century noun defined as "the quality or state of being austere" and "enforced or extreme economy,"

Let's look at Webster's definition for austere:

aus·tere adj \ȯ-ˈstir also -ˈster\

Definition of AUSTERE

1a : stern and cold in appearance or manner b : somber, grave

2: morally strict : ascetic

3: markedly simple or unadorned

4: giving little or no scope for pleasure

5of a wine : having the flavor of acid or tannin predominant over fruit flavors usually indicating a capacity for aging

— aus·tere·ly adverb

— aus·tere·ness noun

Doesn't sound like much fun but is it such a bad thing?

Morally strict... who's morals? Pagan Morals? Would it be such a bad thing, if we were to have Pagan austerity? Where by we only used cloth shopping bags, paid more attention to shopping local whether that was local produced food or arts and crafts or services. If we worked to plant more trees to help with carbon capture? If we worked for bike paths and quality sidewalks that would encourage people to walk more than drive? If we did our best to live lightly on the earth and in the process we lived a simple life and enjoyed life's pleasures, love and each other and the glow of a fire or the warmth of a cup of tea or the way the moonlight can create a soft blue glow? Would that really be so bad?

Friday, December 24, 2010

Louisiana Christmas Traditions

BATON ROUGE, — Louisiana has three traditional Christmas celebrations, says State Archivist Florent Hardy.

In addition to Dec. 25, the date celebrated in Louisiana since 1718, there's St. Nicholas Day on Dec. 5 and the Trappers Christmas in late February.

In New Orleans, the original Christmas celebrations included attending midnight Mass on Christmas Eve.

"At that time, Christmas was a very religious experience," said Hardy. "After Mass was la Reveillon, a big feast that featured a menu of wild game (duck, venison and turkey), daube glace (a jellied meat), eggs, oyster dressing, chuck roast, homemade raisin bread and cakes."

While everyone was at Mass, Papa Noel paid a visit and filled the stockings of the children with a trinket and some fruit and sweets.

"On Christmas day, you visited la creche — the manger scene. Gifts were exchanged on New Year's Day," Hardy told people at the YWCA Connections luncheon in Baton Rouge.

Not everyone gave presents on Christmas. Families of German descent living in

Robert's Cove in Acadia Parish celebrated St. Nicholas Day, gathering at homes to await Kris Kringle and his threatening sidekick, Black Peter, who was said to collect bad children in his sack.

The St. Nicholas Day celebration was suspended around World War II, but has been revived in recent years. These days, a choir accompanies St. Nicholas, Black Peter and Santa Claus to homes in the cove. All the children are given treats, the choir sings German Christmas carols, and sweets and beverages are served.

The Trappers' Christmas in Barataria was late because Christmas was a very busy time of year for the fur trappers, Hardy said.

Santa had a handful of names, depending on what part of Louisiana a person called home. To those of French heritage he was Papa Noel, to those of German heritage he was Kris Kringle or St. Nicholas and to the Cajuns the gift-giving figure was a woman called La Christianne.

"Along the River Road plantations, St. Nicholas arrived on a donkey and left goodies in the shoes of the children left out on the porch," added Hardy.

The familiar Santa who arrives via a sleigh pulled by eight reindeer was created by author Washington Irving in 1819. "He couldn't figure out a way for St. Nicholas to travel around the world in one night, so he came up with this idea of him flying through the trees," said Hardy.

Howard Jacobs created a Louisiana version in "Cajun Night Before Christmas."

"Now in Louisiana, we know Santa, Papa Noel as he's called, comes in a pirogue pulled by eight alligators," Hardy said.

Another tradition in the River Parishes is the Christmas Eve bonfires on the levee, lighting the way for Papa Noel.

"The tradition of the bonfires began with the Marist priests at Jefferson College in Convent," now called Manresa, Hardy said. "It was originally celebrated on New Year's Eve."

What started as simple bonfires in the 1800s grew into such huge creations that their height had to be limited to avoid damage to the levees. Multiple generations join with friends and thousands of complete strangers for a huge celebration.

Further north in Natchitoches, the Festival of Lights has been celebrated since 1927. Begun by the city's superintendent of utilities, today's celebration runs from Nov. 20 through Jan. 6 and draws more than 100,000 visitors. It features more than 300,000 Christmas lights.

In addition to Dec. 25, the date celebrated in Louisiana since 1718, there's St. Nicholas Day on Dec. 5 and the Trappers Christmas in late February.

In New Orleans, the original Christmas celebrations included attending midnight Mass on Christmas Eve.

"At that time, Christmas was a very religious experience," said Hardy. "After Mass was la Reveillon, a big feast that featured a menu of wild game (duck, venison and turkey), daube glace (a jellied meat), eggs, oyster dressing, chuck roast, homemade raisin bread and cakes."

While everyone was at Mass, Papa Noel paid a visit and filled the stockings of the children with a trinket and some fruit and sweets.

"On Christmas day, you visited la creche — the manger scene. Gifts were exchanged on New Year's Day," Hardy told people at the YWCA Connections luncheon in Baton Rouge.

Not everyone gave presents on Christmas. Families of German descent living in

Robert's Cove in Acadia Parish celebrated St. Nicholas Day, gathering at homes to await Kris Kringle and his threatening sidekick, Black Peter, who was said to collect bad children in his sack.

The St. Nicholas Day celebration was suspended around World War II, but has been revived in recent years. These days, a choir accompanies St. Nicholas, Black Peter and Santa Claus to homes in the cove. All the children are given treats, the choir sings German Christmas carols, and sweets and beverages are served.

The Trappers' Christmas in Barataria was late because Christmas was a very busy time of year for the fur trappers, Hardy said.

Santa had a handful of names, depending on what part of Louisiana a person called home. To those of French heritage he was Papa Noel, to those of German heritage he was Kris Kringle or St. Nicholas and to the Cajuns the gift-giving figure was a woman called La Christianne.

"Along the River Road plantations, St. Nicholas arrived on a donkey and left goodies in the shoes of the children left out on the porch," added Hardy.

The familiar Santa who arrives via a sleigh pulled by eight reindeer was created by author Washington Irving in 1819. "He couldn't figure out a way for St. Nicholas to travel around the world in one night, so he came up with this idea of him flying through the trees," said Hardy.

Howard Jacobs created a Louisiana version in "Cajun Night Before Christmas."

"Now in Louisiana, we know Santa, Papa Noel as he's called, comes in a pirogue pulled by eight alligators," Hardy said.

Another tradition in the River Parishes is the Christmas Eve bonfires on the levee, lighting the way for Papa Noel.

"The tradition of the bonfires began with the Marist priests at Jefferson College in Convent," now called Manresa, Hardy said. "It was originally celebrated on New Year's Eve."

What started as simple bonfires in the 1800s grew into such huge creations that their height had to be limited to avoid damage to the levees. Multiple generations join with friends and thousands of complete strangers for a huge celebration.

Further north in Natchitoches, the Festival of Lights has been celebrated since 1927. Begun by the city's superintendent of utilities, today's celebration runs from Nov. 20 through Jan. 6 and draws more than 100,000 visitors. It features more than 300,000 Christmas lights.

Wednesday, December 22, 2010

Stocking Stuffers

For all those kids who have so much... consider these as stocking stuffers.

Fonkoze (fonkoze.org) is a terrific poverty-fighting organization if Haiti is on your mind, nearly a year after the earthquake. A $20 gift will send a rural Haitian child to elementary school for a year, while $50 will buy a family a pregnant goat. Or $100 supports a family for 13 weeks while it starts a business.

Another terrific Haiti-focused organization is Partners in Health, (pih.org), founded by Dr. Paul Farmer, the Harvard Medical School professor. A $100 donation pays for enough therapeutic food (a bit like peanut butter) to treat a severely malnourished child for one month. Or $50 provides seeds, agricultural implements and training for a family to grow more food for itself.

You can donate on line and print out the confirmation and tuck it in a stocking.

Fonkoze (fonkoze.org) is a terrific poverty-fighting organization if Haiti is on your mind, nearly a year after the earthquake. A $20 gift will send a rural Haitian child to elementary school for a year, while $50 will buy a family a pregnant goat. Or $100 supports a family for 13 weeks while it starts a business.

Another terrific Haiti-focused organization is Partners in Health, (pih.org), founded by Dr. Paul Farmer, the Harvard Medical School professor. A $100 donation pays for enough therapeutic food (a bit like peanut butter) to treat a severely malnourished child for one month. Or $50 provides seeds, agricultural implements and training for a family to grow more food for itself.

You can donate on line and print out the confirmation and tuck it in a stocking.

Full Moon in Eclipse Winter Solstice 2010 - New Orleans

Photo Composite by Matthew Hinton / The Times-Picayune

A total eclipse of the moon is seen in this composite of seven photos on the date of the winter solstice by the center spire of the St. Louis Cathedral beginning at just after midnight before becoming totally eclipsed around 2 am in New Orleans, Louisiana Tuesday December 21, 2010. On the first day of northern winter, the full moon passed almost dead-center through Earth's shadow. According to NASA the last total lunar eclipse that happened on the winter solstice was December 21, 1638. The next eclipse on a winter solstice will be December 21, 2094.

Tuesday, December 21, 2010

Monday, December 20, 2010

Written into fiction

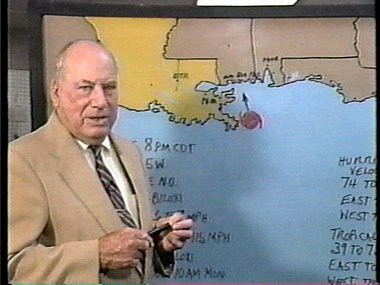

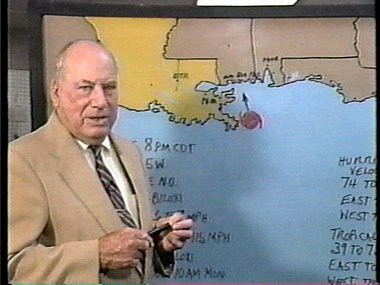

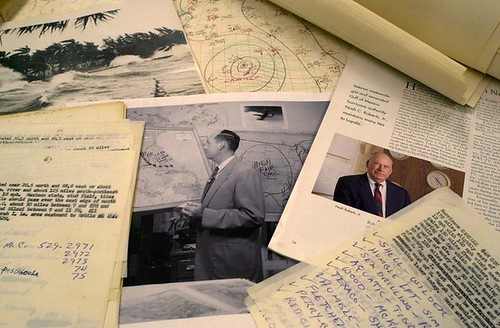

Just a few days ago I put the finishing touches on a chapter that spoke about Nash Roberts and his amazing ability to explain the weather possibilities to regular folk, calm nerves and warn appropriately during hurricane season.

Times-Picayune Staff Video capture photo courtesy of WWL-TV--Nash Roberts, retired weather forecaster at WWL-TV

" "

"

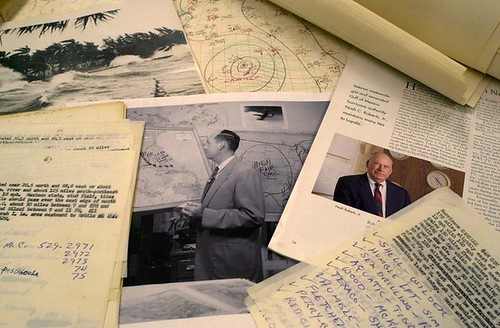

Meteorologist Nash Roberts with his grease pencil

Nash and his maps

Legendary TV weatherman Nash C. Roberts Jr., revered as much for his calm, level-headed presence as the accuracy of his hurricane path projections, has died at age 92, WWL-TV has reported. See Article in full below from Nola.com

For more than 50 years, Gulf Coast weather-watchers relied on Mr. Roberts to tell them where tropical storms would come ashore.

From before Hurricane Betsy in 1965 to beyond Hurricane Georges in 1998, Mr. Roberts was widely considered the region's most authoritative source for hurricane news.

And in the age of Super Doppler and satellite imagery, there remained for hundreds of thousands of New Orleanians a great sense of relief in seeing Mr. Roberts on screen with his throwback bulletin-board-style weather map and felt-tip pens.

"He was old school, but you know what? I miss that," said Bob Breck, chief meteorologist at Fox affiliate WVUE-Channel 8 and a feisty competitor for many years.

Breck said he admired Mr. Roberts' independent approach to forecasting big storms.

"I think Nash wasn't afraid to fail. He trusted his instincts and he just followed his gut. I think that's what people remember him for.

"He was just a man who was a giant of the industry."

Even after his retirement from WWL-TV's nightly newscasts in 1984, Mr. Roberts would reappear on Channel 4 whenever a serious storm entered the Gulf of Mexico.

Bruce Katz, chief meteorologist at WGNO-Channel 26, grew up in New Orleans watching Mr. Roberts' forecasts and hurricane calls.

"He was kind of the inspiration for me doing what I do," Katz said. "Growing up in New Orleans, Nash was the guy. Before the advent of cable TV and satellites, he was the guy everybody turned to.

"He was the legend."

What viewers saw from Mr. Roberts, Katz added, was information and a presentation style from an era that predated today's sophisticated technology.

"His big marker board, the magnetic highs and lows -- it was well before computer technology," Katz said. "You didn't have the data modeling. The science was evolving back then, and he made that interesting."

Mike Hoss, news anchor and interim news director at WWL, came to town in 1989 as a sports anchor well after Mr. Roberts' reputation and loyal following were established.

"Affinity toward him was so strong; it made you, as an outsider, immediately take notice," Hoss said. "And certainly from a technology standpoint, with the greaseboard and the marker, you immediately (and) ever after took notice.

"He spoke to all ages, genders, races, across the board."

In July 2001, Mr. Roberts announced his full retirement, setting aside his black markers to care for his ailing wife, Lydia.

"I actually prayed that I would outlive her, so that I could take care of her," Nash told WWL news anchor Angela Hill at the time. "That's how it's working out."

Mr. Roberts' career in meteorology began in 1946, when he started a private weathercasting service after teaching meteorology at Loyola University and serving as a navigator and meteorologist for the Navy during World War II.

For Texaco and other clients in the oil and gas industry, Mr. Roberts watched the weather over marshes, on the coast and in the Gulf.

In 1951, he began appearing on WDSU as the region's first regular TV weatherman.

Mr. Roberts told Hill in the 2001 interview that he was enticed into the job when he was told about a Chicago forecaster's $80,000 annual salary.

Commenting on Mr. Roberts' premiere, New Orleans Item columnist Ted Liuzza wrote, "He's so unassuming and un-actorish that when he hails you with a shy 'good evening,' you feel like calling back, 'hello.' "

Mr. Roberts cemented his reputation with local viewers by making bull's-eye landfall predictions for Hurricanes Audrey in 1957, Betsy in 1965 and Camille in 1969.

After 22 years with WDSU, Mr. Roberts moved to WVUE, where he stayed until joining WWL in 1978.

Breck had the daunting task of following Mr. Roberts at WVUE, and competing against him after that.

"I was brought to this town to replace Nash," Breck said. "I wanted to beat the old man."

But Breck said he was deeply moved by Mr. Roberts' final retirement in 2001 to care for Lydia.

"He left the love of broadcasting to care for the love of his life," Breck said. "If there's any kind of thing that people should remember about Nash was that he had character. People trusted him."

Mr. Roberts' accurate prediction that Hurricane Georges in 1998 would make landfall east of New Orleans, while all the computer models and other television stations were still insisting Georges would drift to the west, earned him national attention.

"As long as Roberts and his Magic Markers are exclusive to WWL," The Times-Picayune wrote after Georges, "Channel 4 will remain the only place to get an answer to the first hurricane-related question asked by anyone who's lived in New Orleans for any length of time: 'What's Nash say?' "

Mr. Roberts and his wife stayed in town for every hurricane -- he at the station, she at home in Metairie -- until Hurricane Katrina.

Mr. Roberts told Times-Picayune TV columnist Dave Walker in 2006 that it was a joke on his block: During a hurricane threat, neighbors would wait for his wife's car to leave before they'd evacuate. Until Katrina, it never happened.

"I left my wife at home, and she rode out every one of them right here," Mr. Roberts said. "I wouldn't have let that happen if I thought it was dangerous. The story in the neighborhood was, 'I'm staying here unless I look out the window and Lydia's car is gone. If Nash tells Lydia to leave, we're all leaving.' "Katrina, which struck when Mr. Roberts was fully retired, was different.

"For the first time in 60 years, I evacuated," Mr. Roberts said in 2006. "I was pretty sure the thing was coming in here. What convinced me that I better get out was the fact that I knew it was going to be a wet system. It was huge in size, driving a lot of water ahead of it. With my wife, with the condition she's in, I said, 'We'd better get out of here.' ''

The couple evacuated from their Metairie home to Baton Rouge for two months. Their home sustained minimal damage.

"As soon as they would let me, I went to the gap in the 17th Street Canal and looked it over, and then I worked my way through Lakeview and lower New Orleans," Mr. Roberts told Walker. "It just was breathtaking, spooky. To go through neighborhoods and never see anybody, just a bunch of old beat-up cars and nobody living in any of the houses."

Despite occasional pangs of professional nostalgia, Mr. Roberts said he was glad he wasn't at WWL's studio tracking Katrina's path to town via squeaky pen and wipe-board.

"The truth of the whole matter is I'm glad I wasn't on for this," he said. "It would've been a very, very trying and tiring ordeal. My method of fooling with these storms is I lock onto 'em and just stay with 'em 24 hours a day, seven days a week, until they're gone, and that is extremely arduous.

"But I could've done very little for anybody with this storm except do what I did. I left (with Lydia) on Saturday."

Lydia Roberts died in 2007, according to WWL. The couple had been married more than 60 years.

Mr. Roberts figured prominently in a 2006 book from Kensington Publishing, "Roar of the Heavens: Surviving Hurricane Camille," by Stefan Bechtel.

"A wonderful man," Bechtel said. "Kind of courtly, gentlemanly. We spent quite a long time talking, and he started making me little maps with what is now a rather shaky hand, like a football coach calling the plays."

To WWL's Hoss, Mr. Roberts' longevity on local airwaves was as remarkable as his forecasting prowess.

"You don't get to do five decades if you aren't respected," Hoss said. "You don't get to do five decades unless you do it right.

"Quite frankly, he did it right."

Survivors include two sons, Kenneth and Nash Roberts III; three brothers; and four grandchildren, WWL said.

Funeral arrangements are incomplete.

••••••••

TV Columnist Dave Walker contributed to this article, which was prepared by staff writer Stephanie Stokes.

Times-Picayune Staff Video capture photo courtesy of WWL-TV--Nash Roberts, retired weather forecaster at WWL-TV

"

"

"Meteorologist Nash Roberts with his grease pencil

Nash and his maps

Legendary TV weatherman Nash C. Roberts Jr., revered as much for his calm, level-headed presence as the accuracy of his hurricane path projections, has died at age 92, WWL-TV has reported. See Article in full below from Nola.com

For more than 50 years, Gulf Coast weather-watchers relied on Mr. Roberts to tell them where tropical storms would come ashore.

From before Hurricane Betsy in 1965 to beyond Hurricane Georges in 1998, Mr. Roberts was widely considered the region's most authoritative source for hurricane news.

And in the age of Super Doppler and satellite imagery, there remained for hundreds of thousands of New Orleanians a great sense of relief in seeing Mr. Roberts on screen with his throwback bulletin-board-style weather map and felt-tip pens.

"He was old school, but you know what? I miss that," said Bob Breck, chief meteorologist at Fox affiliate WVUE-Channel 8 and a feisty competitor for many years.

Breck said he admired Mr. Roberts' independent approach to forecasting big storms.

"I think Nash wasn't afraid to fail. He trusted his instincts and he just followed his gut. I think that's what people remember him for.

"He was just a man who was a giant of the industry."

Even after his retirement from WWL-TV's nightly newscasts in 1984, Mr. Roberts would reappear on Channel 4 whenever a serious storm entered the Gulf of Mexico.

Bruce Katz, chief meteorologist at WGNO-Channel 26, grew up in New Orleans watching Mr. Roberts' forecasts and hurricane calls.

"He was kind of the inspiration for me doing what I do," Katz said. "Growing up in New Orleans, Nash was the guy. Before the advent of cable TV and satellites, he was the guy everybody turned to.

"He was the legend."

What viewers saw from Mr. Roberts, Katz added, was information and a presentation style from an era that predated today's sophisticated technology.

"His big marker board, the magnetic highs and lows -- it was well before computer technology," Katz said. "You didn't have the data modeling. The science was evolving back then, and he made that interesting."

Mike Hoss, news anchor and interim news director at WWL, came to town in 1989 as a sports anchor well after Mr. Roberts' reputation and loyal following were established.

"Affinity toward him was so strong; it made you, as an outsider, immediately take notice," Hoss said. "And certainly from a technology standpoint, with the greaseboard and the marker, you immediately (and) ever after took notice.

"He spoke to all ages, genders, races, across the board."

In July 2001, Mr. Roberts announced his full retirement, setting aside his black markers to care for his ailing wife, Lydia.

"I actually prayed that I would outlive her, so that I could take care of her," Nash told WWL news anchor Angela Hill at the time. "That's how it's working out."

Mr. Roberts' career in meteorology began in 1946, when he started a private weathercasting service after teaching meteorology at Loyola University and serving as a navigator and meteorologist for the Navy during World War II.

For Texaco and other clients in the oil and gas industry, Mr. Roberts watched the weather over marshes, on the coast and in the Gulf.

In 1951, he began appearing on WDSU as the region's first regular TV weatherman.

Mr. Roberts told Hill in the 2001 interview that he was enticed into the job when he was told about a Chicago forecaster's $80,000 annual salary.

Commenting on Mr. Roberts' premiere, New Orleans Item columnist Ted Liuzza wrote, "He's so unassuming and un-actorish that when he hails you with a shy 'good evening,' you feel like calling back, 'hello.' "

Mr. Roberts cemented his reputation with local viewers by making bull's-eye landfall predictions for Hurricanes Audrey in 1957, Betsy in 1965 and Camille in 1969.

After 22 years with WDSU, Mr. Roberts moved to WVUE, where he stayed until joining WWL in 1978.

Breck had the daunting task of following Mr. Roberts at WVUE, and competing against him after that.

"I was brought to this town to replace Nash," Breck said. "I wanted to beat the old man."

But Breck said he was deeply moved by Mr. Roberts' final retirement in 2001 to care for Lydia.

"He left the love of broadcasting to care for the love of his life," Breck said. "If there's any kind of thing that people should remember about Nash was that he had character. People trusted him."

Mr. Roberts' accurate prediction that Hurricane Georges in 1998 would make landfall east of New Orleans, while all the computer models and other television stations were still insisting Georges would drift to the west, earned him national attention.

"As long as Roberts and his Magic Markers are exclusive to WWL," The Times-Picayune wrote after Georges, "Channel 4 will remain the only place to get an answer to the first hurricane-related question asked by anyone who's lived in New Orleans for any length of time: 'What's Nash say?' "

Mr. Roberts and his wife stayed in town for every hurricane -- he at the station, she at home in Metairie -- until Hurricane Katrina.

Mr. Roberts told Times-Picayune TV columnist Dave Walker in 2006 that it was a joke on his block: During a hurricane threat, neighbors would wait for his wife's car to leave before they'd evacuate. Until Katrina, it never happened.

"I left my wife at home, and she rode out every one of them right here," Mr. Roberts said. "I wouldn't have let that happen if I thought it was dangerous. The story in the neighborhood was, 'I'm staying here unless I look out the window and Lydia's car is gone. If Nash tells Lydia to leave, we're all leaving.' "Katrina, which struck when Mr. Roberts was fully retired, was different.

"For the first time in 60 years, I evacuated," Mr. Roberts said in 2006. "I was pretty sure the thing was coming in here. What convinced me that I better get out was the fact that I knew it was going to be a wet system. It was huge in size, driving a lot of water ahead of it. With my wife, with the condition she's in, I said, 'We'd better get out of here.' ''

The couple evacuated from their Metairie home to Baton Rouge for two months. Their home sustained minimal damage.

"As soon as they would let me, I went to the gap in the 17th Street Canal and looked it over, and then I worked my way through Lakeview and lower New Orleans," Mr. Roberts told Walker. "It just was breathtaking, spooky. To go through neighborhoods and never see anybody, just a bunch of old beat-up cars and nobody living in any of the houses."

Despite occasional pangs of professional nostalgia, Mr. Roberts said he was glad he wasn't at WWL's studio tracking Katrina's path to town via squeaky pen and wipe-board.

"The truth of the whole matter is I'm glad I wasn't on for this," he said. "It would've been a very, very trying and tiring ordeal. My method of fooling with these storms is I lock onto 'em and just stay with 'em 24 hours a day, seven days a week, until they're gone, and that is extremely arduous.

"But I could've done very little for anybody with this storm except do what I did. I left (with Lydia) on Saturday."

Lydia Roberts died in 2007, according to WWL. The couple had been married more than 60 years.

Mr. Roberts figured prominently in a 2006 book from Kensington Publishing, "Roar of the Heavens: Surviving Hurricane Camille," by Stefan Bechtel.

"A wonderful man," Bechtel said. "Kind of courtly, gentlemanly. We spent quite a long time talking, and he started making me little maps with what is now a rather shaky hand, like a football coach calling the plays."

To WWL's Hoss, Mr. Roberts' longevity on local airwaves was as remarkable as his forecasting prowess.

"You don't get to do five decades if you aren't respected," Hoss said. "You don't get to do five decades unless you do it right.

"Quite frankly, he did it right."

Survivors include two sons, Kenneth and Nash Roberts III; three brothers; and four grandchildren, WWL said.

Funeral arrangements are incomplete.

••••••••

TV Columnist Dave Walker contributed to this article, which was prepared by staff writer Stephanie Stokes.

Sunday, December 19, 2010

Apocalypse Soon?

Apocalypse Soon?

Volume 62 Number 6, November/December 2009 by Anthony Aveni

What the Maya calendar really tells us about 2012 and the end of time

On December 21, 2012, thousands of pilgrims, many in organized "sacred tour" groups, will flock to Chichén Itzá, Tikal, and a multitude of other celebrated sites of ancient America. There they will wait for a sign from the ancient Maya marking the end of the world as we know it. Will it be a blow-up or a bliss-out? Doom or delight? That depends on which of the New Age prophets--an eclectic collection of self-appointed seers and mystics, with names such as "Valum Votan, closer of the cycle" and the "Cosmic Shaman of Galactic Structure"--one chooses to believe. In 2012, the grand odometer of Maya timekeeping known as the Long Count, an accumulation of various smaller time cycles, will revert to zero and a new cycle of 1,872,000 days (5,125.37 years) will begin. As the long-awaited "Y12" date nears, tales of what will happen are proliferating on the Internet, in print, and in movies: Hollywood's big-budget, effects-laden disaster epic, "2012," opens this November under the tagline "We Were Warned."

Many of the predictions begin in outer space. It's known that there is a black hole at the center of the Milky Way, and that in 2012 the sun will align with the plane of the Galaxy for the first time in 26,000 years. Then, according to the doomsayers, the black hole will throw our solar system out of kilter. Lawrence E. Joseph, author of a book called Apocalypse 2012, says that supergiant flares will erupt on the sun's surface, propelling an extraordinary plume of solar particles earthward at the next peak of solar activity. Earth's magnetic field will reverse, producing dire consequences such as violent hurricanes and the loss of all electronic communication systems. And recent natural disasters, from Hurricane Katrina to the Indian Ocean tsunami? They are all related to this alignment, and the ancient Maya knew all about it. That's the bad news.

But there's also good news coming from Y12 visionaries. Some say that rather than cataclysm, we're due for a sudden, cosmically timed awakening; we will all join an enlightened collective consciousness that will resolve the world's problems. The winter solstice sun is "slowly moving toward the heart of the Galaxy," writes spiritualist and former software engineer John Major Jenkins. On December 21 (or 23, depending on how you align calendars), when the sun passes the "Great Rift," a dark streak in the Milky Way that Jenkins says represents the Maya "Womb of Creation," the world will be transformed. Then we will "reconnect with our cosmic heart," he writes.

Unwittingly, the ancient Maya provided fodder for all this cosmic rigmarole. Monuments, such as Stela 25 at Izapa, a peripheral, pre-Classic (ca. 400 B.C.) site located on Mexico's Pacific Coast, map out the galactic alignment that would mark the end of the Long Count. Stela 25, for example, is thought to depict a creation scene in which a bird deity is perched atop a cosmic tree. Jenkins thinks the tree represents a unique north-south alignment of the Milky Way--a message from the Maya of what the sky will look like when creation begins anew.

These head-turning forecasts are open to serious criticism on both cultural and scientific grounds. There is little evidence that the Maya cared much about the Milky Way. When they do refer to it, they usually imagine it as a road. The association of the Milky Way with a tree, despite the popularity it has acquired since the publication of the 1997 book Maya Cosmos by noted Maya scholars David Freidel and Linda Schele, and writer Joy Parker, emerges strictly from the study of contemporary cultures descended from the Maya.

From an astronomical perspective, the 26,000-year cycle that causes the realignment of the sun with the plane of the Milky Way was first described by Greek astronomer Hipparchus in 128 B.C. He observed a slight difference between the solar year (the time it takes the earth to revolve around the sun) and the stellar or sidereal year (the time it takes the sun to realign with the stars). As a result, year to year, the path of the sun and the spots where it rises and sets will change with respect to the backdrop of the stars. This phenomenon, called precession, is caused by the gradual shift of the earth's axis of rotation. In practice, it means that the position of the sun at equinoxes and solstices, which mark the seasons, slowly changes with respect to the constellations of the zodiac. Maya skywatchers possessed a zodiac, so they could have noted the difference between stellar years and solar years, but there is no convincing evidence that they charted the precession, or how they might have done it.

According to the Y12ers, based on their interpretation of monuments such as Stela 25, the Maya not only tracked the precession, but used it to predict what the sky would look like when the Long Count ends and a new cycle of creation begins. However, anyone who takes the trouble to look at the nighttime sky will discover that the Milky Way, a broad, luminous swath across the sky, looks surprisingly little like it is depicted in the desktop planetarium software often used to infer what ancient stargazers saw. For example, the galactic plane is very difficult to define even when the sun isn't in it, so solar-galactic alignment can't be pinned down visually to an accuracy any better than 300 years. Also, the "unique" north-south orientation of the Milky Way thought to be portrayed on Stela 25 actually occurs every year. And more important conceptually, there is no evidence that the Maya used sky maps as representational devices the way we do. Finally, there is no indication the Maya cared a whit about solar flares, sunspots, or magnetic fields. Pulling prophecy from monuments such as Stela 25 amounts to an exercise in cherry-picking data--often incomplete, vague, or inapplicable--to justify a nonsensical, pre-formed idea.

Most people familiar with the ancient Maya--even those who are not prophets of doom--know that they were obsessed with sophisticated timekeeping systems. And it is clear from their painted-bark books, or codices, that their astronomers had the capacity to predict celestial events, such as eclipses, accurately. So it is no surprise that mystically minded people feel free to attribute to the ancient Maya the power to see far into the future. But what does the cultural record actually tell us about the nature of Maya timekeeping and its relationship to their ideas about creation?

By the beginning of the Classic Period (ca. A.D. 200), Maya polities had mastered cultivation of the land, expanded their states, and begun to build great cities with exquisite monumental architecture. They were on the verge of establishing one of the great civilizations of the ancient world. A few hundred years earlier, Maya rulers had made a fundamental revision to their calendar that would connect the rise of Maya states with their own origin myths. They invented a mountain of a time cycle--the Long Count. A brilliant innovation, it transplanted the roots of Maya culture all the way back to creation itself. The Long Count was established with their existing base-20 counting system, with the day as the basic unit (see above). It consists of 13 cycles--corresponding to the levels of Maya heaven, each occupied by objects and deities associated with celestial bodies--called baktuns that make up a creation period of 5,125.37 seasonal years. At the end of one creation cycle, the count rolls over to the next Day Zero.

Texts carved on stelae prominently displayed at many Maya sites often open with a Long Count date, a series of five numbers (12.8.0.1.13, for example, corresponds to July 4, 1776) similar to the dateline in a newspaper. These time markers were a form of political and religious propaganda. Maya rulers used them to link culturally important but cosmically mundane events in their personal histories--coronation dates, marriage alliances, military victories, and the turning of smaller time cycles (for instance, 9.15.0.0.0, the inscription on Copán's Stela B, marks the end of a katun, or 20-year cycle)--with the history of their ancestor-gods who created the world. Thus, a stela's Long Count gave the ruler the power to proclaim the extraordinary longevity of his bloodline in concrete terms.

The beginning of the Long Count, which marks the last creation episode, took place in the Maya's mythic past. Day Zero fell on August 11, 3114 B.C. That date was denoted as 13.0.0.0.0, which is the same date we will see 13 baktuns later, when the Long Count rolls over from 12.19.19.17.19 on December 21, 2012, the next Day Zero (give or take a day). August 11 falls close to one of the two dates each year when the sun passes directly overhead in southern Maya latitudes--an event known to have been important in the Maya world. December 21 or 22 is the winter solstice (or solar "standstill"), which marks the day the sun reaches its most southerly position in the sky. So it is conceivable that the past and future zero days or creation events were deliberately linked to important positions in the sun cycle.

Why does the Long Count begin in 3114 B.C., well before any identifiably Maya culture had been established by the archaic communities that lived there? If we follow the example of how zero dates were set in other calendars around the world, such as the Christian, Roman, and Sanskrit ones, the choice was likely either an arbitrary date linked to some more recent event in Maya history, or itself a culturally and historically significant moment (similar to the way that the putative year of the birth of Christ roughly marks the beginning of the Christian calendar). But there was nothing special about the position of the Milky Way or the zodiac on that date, nor was anything significant happening in the sky. The Maya may simply have selected some date from which to look back to decide where their own creation date would fall. One possible date for this jumping off point is 7.6.0.0.0 (236 B.C.), which falls right around the time of the earliest Long Count inscriptions. That date also marks the end of a katun and bears the same Maya month and day names as the date of creation. It is amusing that the Y12 prophets are certain the world will end for all of us based on a date that may or may not have had historical significance to the Maya a few thousand years ago, who were themselves looking to a date a few thousand years before that. The ancient Maya might tell us: "Hey, get your own zero point!"

Though the Maya believed that successive creations were cyclic, there is no clear evidence of what they thought would happen on our 13.0.0.0.0. The same holds true for what happened last time the odometer of creation turned over. But a menacing scene does appear on the last page of the Dresden Codex, a Maya bark-paper book from the 14th century A.D., depicting destruction by flood. A sky caiman vomits water, which gushes from "sun" and "moon" glyphs attached to the beast's segmented body. Still more water pours out of a vessel held by an old-woman deity, who is suspended in the middle of the frame. And at the bottom, a male deity wields arrows and a spear. Verses from early colonial texts back up the flood story of creation. Curiously, contemporary prophets of doom haven't seized on the flood myth as a mode of destruction, though moviemakers certainly have. Among the vivid special effects in 2012 are tsunamis engulfing the Himalayas and tossing an aircraft carrier into the White House!

Monumental Maya inscriptions are fairly silent regarding events of the previous creation. Stela C at Quiriguá in Guatemala follows its 13.0.0.0.0 inscription with hieroglyphic statements that refer to the descent of deities (related to Cauac Sky, the extant ruler, of course), who create the first hearth by setting up three support stones (represented in the sky by parts of the constellation Orion). Concerning our 13.0.0.0.0, Monument 6 at Tortuguero in the Mexican state of Tabasco tells of the descent of some transcendent entity to earth. But just when the story might get even more interesting, the glyphs have eroded away, leaving the door open for the prophets to continue to speculate.

Must we read real history (and the future) in the Maya narratives? Or can we see them as frameworks for the cultural transmission of traditional rites of renewal, which take place at the turn of all time cycles, such as the appearance and disappearance of Venus, or the 52-year calendar round that combines the seasonal year with the Maya 260-day sacred calendar? Every year we participate in such rituals on New Year's Eve. We take account of ourselves by celebrating the end of our seasonal cycle--often with wretched excess--as the stroke of midnight approaches. Then we perform our acts of penance (New Year's resolutions) to purify ourselves as we contemplate a brighter future. A vast majority of those familiar with the Maya culture view their cycle-ending prophecies as lessons on how to restore balance to the world by promoting reciprocity with the gods, such as offering them debt payments in exchange for fertile crops. No wonder we are inspired by the Maya--they get to participate in their cosmology! But in that sense, the Y12ers are not so different from the ancient Maya in their desire to reconnect with the past and place their own existence in a broader context. Where the Maya tied themselves to their ancestor-gods by carving Long Count dates on their stelae, the Y12 prophets use Maya myth and math to invoke some sort of universal beneficent spirit or transcendent evil overmind.

There is also something about the Y12 hysteria that is particular to the English-speaking world--especially the United States. The idea that the world will end in cataclysm was firmly planted in Puritan New England. Evangelical and apocalyptic forms of worship were prominent in the colonies as early as the 1640s, when confessors openly proclaimed themselves ready for God to descend from the sky and pluck them up for judgment. Two centuries later, hundreds of Millerites (who would become the Seventh-day Adventists) anxiously awaited the "Blessed Hope," based on their leader William Miller's biblical calculations pinpointing the return of Christ on October 22, 1844. People climbed to their roofs to wait--and wait--for the Second Coming.

Today, American anticipation of a celestially signaled end of time has gone mainstream secular. Many of us remember Comet Kohoutek, the iceball sent to destroy the world in 1973, or the millennial cosmic reclamation project that attended Comet Hale-Bopp in 1997--an "alien mothership" that brought the suicides of 39 members of the Heaven's Gate cult in California. The celebrated cosmic convergence of Aztec calendar cycles in 1987 is another example of the American desire to get beamed with revelations from beyond.

It is no coincidence that the Maya entered the modern mythos of creation and destruction in the early 1970s, around the time scholars began to make significant breakthroughs in deciphering Maya hieroglyphics. Repeating a trend started a century earlier with the mystical writing of Augustus Le Plongeon ('The Lure of Moo,' January/February 2007), pop-fringe literature such as Peter Tompkins's Secrets of the Mexican Pyramids, Frank Waters's Mexico Mystique, and Luis Arochi's The Pyramid of Kukulcan heralded secret knowledge of the future emerging from the Maya code. It was also about this time that promoting the idea of "shared beginnings," acquired by being at the right place at the right time, began to enter the tourism industry. Tourists, many with New Age spiritual leanings, flock to Chichén Itzá on the spring equinox, for example, to see a serpent effigy emerge in the shadows of El Castillo. Sacred tourism is already beginning to cash in on the 2012 myth. Star parties are planned for Copán and Tikal on the eve of the temporal turnover. And industrious entrepreneurs are already beginning to prepare 2012 survival kits, a Complete Idiot's Guide to 2012, and T-shirts bearing slogans such as "Doomsday 2012" and "Shift Happens." Not to mention the movie. This is just the beginning.

We live in a techno-immersed, materially oriented society that seems somewhat bewildered by where rational, empirical science might be taking us. This may be why the mystical, escapist explanations of a galactic endpoint, replete with precise mathematical, historical, and cosmic underpinnings (masquerading as science), have such wide appeal. In an age of anxiety we reach for the wisdom of ancestors--even other peoples' ancestors--that might have been lost in the drifting sands of time. Perhaps the only way we can take back control of our disordered world is to rediscover their lost knowledge and make use of it. And so we romanticize the ancient Maya.

But the glorious achievements of the Maya and other complex cultures of the ancient world are appealing enough on their own. We don't need to dress them up in Western or apocalyptic clothing. And the responsibility for educating the public about what we really know about the Maya and other extraordinary cultures--such as the ability of the Maya to follow the position of Venus to an accuracy of one day in 500 years with the naked eye--should fall squarely on the shoulders of those of us who spend our lives studying them. The Y12 hysteria could leave us asking whether we are doing our jobs, or whether the desire for cosmic connection and continuity is too strong for science and rationality to overcome.

Anthony Aveni is the Russell Colgate professor of astronomy and anthropology at Colgate University and author of the new book, The End of Time: The Maya Mystery of 2012.

Volume 62 Number 6, November/December 2009 by Anthony Aveni

What the Maya calendar really tells us about 2012 and the end of time

On December 21, 2012, thousands of pilgrims, many in organized "sacred tour" groups, will flock to Chichén Itzá, Tikal, and a multitude of other celebrated sites of ancient America. There they will wait for a sign from the ancient Maya marking the end of the world as we know it. Will it be a blow-up or a bliss-out? Doom or delight? That depends on which of the New Age prophets--an eclectic collection of self-appointed seers and mystics, with names such as "Valum Votan, closer of the cycle" and the "Cosmic Shaman of Galactic Structure"--one chooses to believe. In 2012, the grand odometer of Maya timekeeping known as the Long Count, an accumulation of various smaller time cycles, will revert to zero and a new cycle of 1,872,000 days (5,125.37 years) will begin. As the long-awaited "Y12" date nears, tales of what will happen are proliferating on the Internet, in print, and in movies: Hollywood's big-budget, effects-laden disaster epic, "2012," opens this November under the tagline "We Were Warned."

Many of the predictions begin in outer space. It's known that there is a black hole at the center of the Milky Way, and that in 2012 the sun will align with the plane of the Galaxy for the first time in 26,000 years. Then, according to the doomsayers, the black hole will throw our solar system out of kilter. Lawrence E. Joseph, author of a book called Apocalypse 2012, says that supergiant flares will erupt on the sun's surface, propelling an extraordinary plume of solar particles earthward at the next peak of solar activity. Earth's magnetic field will reverse, producing dire consequences such as violent hurricanes and the loss of all electronic communication systems. And recent natural disasters, from Hurricane Katrina to the Indian Ocean tsunami? They are all related to this alignment, and the ancient Maya knew all about it. That's the bad news.

But there's also good news coming from Y12 visionaries. Some say that rather than cataclysm, we're due for a sudden, cosmically timed awakening; we will all join an enlightened collective consciousness that will resolve the world's problems. The winter solstice sun is "slowly moving toward the heart of the Galaxy," writes spiritualist and former software engineer John Major Jenkins. On December 21 (or 23, depending on how you align calendars), when the sun passes the "Great Rift," a dark streak in the Milky Way that Jenkins says represents the Maya "Womb of Creation," the world will be transformed. Then we will "reconnect with our cosmic heart," he writes.

Unwittingly, the ancient Maya provided fodder for all this cosmic rigmarole. Monuments, such as Stela 25 at Izapa, a peripheral, pre-Classic (ca. 400 B.C.) site located on Mexico's Pacific Coast, map out the galactic alignment that would mark the end of the Long Count. Stela 25, for example, is thought to depict a creation scene in which a bird deity is perched atop a cosmic tree. Jenkins thinks the tree represents a unique north-south alignment of the Milky Way--a message from the Maya of what the sky will look like when creation begins anew.

These head-turning forecasts are open to serious criticism on both cultural and scientific grounds. There is little evidence that the Maya cared much about the Milky Way. When they do refer to it, they usually imagine it as a road. The association of the Milky Way with a tree, despite the popularity it has acquired since the publication of the 1997 book Maya Cosmos by noted Maya scholars David Freidel and Linda Schele, and writer Joy Parker, emerges strictly from the study of contemporary cultures descended from the Maya.

From an astronomical perspective, the 26,000-year cycle that causes the realignment of the sun with the plane of the Milky Way was first described by Greek astronomer Hipparchus in 128 B.C. He observed a slight difference between the solar year (the time it takes the earth to revolve around the sun) and the stellar or sidereal year (the time it takes the sun to realign with the stars). As a result, year to year, the path of the sun and the spots where it rises and sets will change with respect to the backdrop of the stars. This phenomenon, called precession, is caused by the gradual shift of the earth's axis of rotation. In practice, it means that the position of the sun at equinoxes and solstices, which mark the seasons, slowly changes with respect to the constellations of the zodiac. Maya skywatchers possessed a zodiac, so they could have noted the difference between stellar years and solar years, but there is no convincing evidence that they charted the precession, or how they might have done it.

According to the Y12ers, based on their interpretation of monuments such as Stela 25, the Maya not only tracked the precession, but used it to predict what the sky would look like when the Long Count ends and a new cycle of creation begins. However, anyone who takes the trouble to look at the nighttime sky will discover that the Milky Way, a broad, luminous swath across the sky, looks surprisingly little like it is depicted in the desktop planetarium software often used to infer what ancient stargazers saw. For example, the galactic plane is very difficult to define even when the sun isn't in it, so solar-galactic alignment can't be pinned down visually to an accuracy any better than 300 years. Also, the "unique" north-south orientation of the Milky Way thought to be portrayed on Stela 25 actually occurs every year. And more important conceptually, there is no evidence that the Maya used sky maps as representational devices the way we do. Finally, there is no indication the Maya cared a whit about solar flares, sunspots, or magnetic fields. Pulling prophecy from monuments such as Stela 25 amounts to an exercise in cherry-picking data--often incomplete, vague, or inapplicable--to justify a nonsensical, pre-formed idea.

Most people familiar with the ancient Maya--even those who are not prophets of doom--know that they were obsessed with sophisticated timekeeping systems. And it is clear from their painted-bark books, or codices, that their astronomers had the capacity to predict celestial events, such as eclipses, accurately. So it is no surprise that mystically minded people feel free to attribute to the ancient Maya the power to see far into the future. But what does the cultural record actually tell us about the nature of Maya timekeeping and its relationship to their ideas about creation?

By the beginning of the Classic Period (ca. A.D. 200), Maya polities had mastered cultivation of the land, expanded their states, and begun to build great cities with exquisite monumental architecture. They were on the verge of establishing one of the great civilizations of the ancient world. A few hundred years earlier, Maya rulers had made a fundamental revision to their calendar that would connect the rise of Maya states with their own origin myths. They invented a mountain of a time cycle--the Long Count. A brilliant innovation, it transplanted the roots of Maya culture all the way back to creation itself. The Long Count was established with their existing base-20 counting system, with the day as the basic unit (see above). It consists of 13 cycles--corresponding to the levels of Maya heaven, each occupied by objects and deities associated with celestial bodies--called baktuns that make up a creation period of 5,125.37 seasonal years. At the end of one creation cycle, the count rolls over to the next Day Zero.

Texts carved on stelae prominently displayed at many Maya sites often open with a Long Count date, a series of five numbers (12.8.0.1.13, for example, corresponds to July 4, 1776) similar to the dateline in a newspaper. These time markers were a form of political and religious propaganda. Maya rulers used them to link culturally important but cosmically mundane events in their personal histories--coronation dates, marriage alliances, military victories, and the turning of smaller time cycles (for instance, 9.15.0.0.0, the inscription on Copán's Stela B, marks the end of a katun, or 20-year cycle)--with the history of their ancestor-gods who created the world. Thus, a stela's Long Count gave the ruler the power to proclaim the extraordinary longevity of his bloodline in concrete terms.

The beginning of the Long Count, which marks the last creation episode, took place in the Maya's mythic past. Day Zero fell on August 11, 3114 B.C. That date was denoted as 13.0.0.0.0, which is the same date we will see 13 baktuns later, when the Long Count rolls over from 12.19.19.17.19 on December 21, 2012, the next Day Zero (give or take a day). August 11 falls close to one of the two dates each year when the sun passes directly overhead in southern Maya latitudes--an event known to have been important in the Maya world. December 21 or 22 is the winter solstice (or solar "standstill"), which marks the day the sun reaches its most southerly position in the sky. So it is conceivable that the past and future zero days or creation events were deliberately linked to important positions in the sun cycle.

Why does the Long Count begin in 3114 B.C., well before any identifiably Maya culture had been established by the archaic communities that lived there? If we follow the example of how zero dates were set in other calendars around the world, such as the Christian, Roman, and Sanskrit ones, the choice was likely either an arbitrary date linked to some more recent event in Maya history, or itself a culturally and historically significant moment (similar to the way that the putative year of the birth of Christ roughly marks the beginning of the Christian calendar). But there was nothing special about the position of the Milky Way or the zodiac on that date, nor was anything significant happening in the sky. The Maya may simply have selected some date from which to look back to decide where their own creation date would fall. One possible date for this jumping off point is 7.6.0.0.0 (236 B.C.), which falls right around the time of the earliest Long Count inscriptions. That date also marks the end of a katun and bears the same Maya month and day names as the date of creation. It is amusing that the Y12 prophets are certain the world will end for all of us based on a date that may or may not have had historical significance to the Maya a few thousand years ago, who were themselves looking to a date a few thousand years before that. The ancient Maya might tell us: "Hey, get your own zero point!"

Though the Maya believed that successive creations were cyclic, there is no clear evidence of what they thought would happen on our 13.0.0.0.0. The same holds true for what happened last time the odometer of creation turned over. But a menacing scene does appear on the last page of the Dresden Codex, a Maya bark-paper book from the 14th century A.D., depicting destruction by flood. A sky caiman vomits water, which gushes from "sun" and "moon" glyphs attached to the beast's segmented body. Still more water pours out of a vessel held by an old-woman deity, who is suspended in the middle of the frame. And at the bottom, a male deity wields arrows and a spear. Verses from early colonial texts back up the flood story of creation. Curiously, contemporary prophets of doom haven't seized on the flood myth as a mode of destruction, though moviemakers certainly have. Among the vivid special effects in 2012 are tsunamis engulfing the Himalayas and tossing an aircraft carrier into the White House!

Monumental Maya inscriptions are fairly silent regarding events of the previous creation. Stela C at Quiriguá in Guatemala follows its 13.0.0.0.0 inscription with hieroglyphic statements that refer to the descent of deities (related to Cauac Sky, the extant ruler, of course), who create the first hearth by setting up three support stones (represented in the sky by parts of the constellation Orion). Concerning our 13.0.0.0.0, Monument 6 at Tortuguero in the Mexican state of Tabasco tells of the descent of some transcendent entity to earth. But just when the story might get even more interesting, the glyphs have eroded away, leaving the door open for the prophets to continue to speculate.

Must we read real history (and the future) in the Maya narratives? Or can we see them as frameworks for the cultural transmission of traditional rites of renewal, which take place at the turn of all time cycles, such as the appearance and disappearance of Venus, or the 52-year calendar round that combines the seasonal year with the Maya 260-day sacred calendar? Every year we participate in such rituals on New Year's Eve. We take account of ourselves by celebrating the end of our seasonal cycle--often with wretched excess--as the stroke of midnight approaches. Then we perform our acts of penance (New Year's resolutions) to purify ourselves as we contemplate a brighter future. A vast majority of those familiar with the Maya culture view their cycle-ending prophecies as lessons on how to restore balance to the world by promoting reciprocity with the gods, such as offering them debt payments in exchange for fertile crops. No wonder we are inspired by the Maya--they get to participate in their cosmology! But in that sense, the Y12ers are not so different from the ancient Maya in their desire to reconnect with the past and place their own existence in a broader context. Where the Maya tied themselves to their ancestor-gods by carving Long Count dates on their stelae, the Y12 prophets use Maya myth and math to invoke some sort of universal beneficent spirit or transcendent evil overmind.

There is also something about the Y12 hysteria that is particular to the English-speaking world--especially the United States. The idea that the world will end in cataclysm was firmly planted in Puritan New England. Evangelical and apocalyptic forms of worship were prominent in the colonies as early as the 1640s, when confessors openly proclaimed themselves ready for God to descend from the sky and pluck them up for judgment. Two centuries later, hundreds of Millerites (who would become the Seventh-day Adventists) anxiously awaited the "Blessed Hope," based on their leader William Miller's biblical calculations pinpointing the return of Christ on October 22, 1844. People climbed to their roofs to wait--and wait--for the Second Coming.

Today, American anticipation of a celestially signaled end of time has gone mainstream secular. Many of us remember Comet Kohoutek, the iceball sent to destroy the world in 1973, or the millennial cosmic reclamation project that attended Comet Hale-Bopp in 1997--an "alien mothership" that brought the suicides of 39 members of the Heaven's Gate cult in California. The celebrated cosmic convergence of Aztec calendar cycles in 1987 is another example of the American desire to get beamed with revelations from beyond.

It is no coincidence that the Maya entered the modern mythos of creation and destruction in the early 1970s, around the time scholars began to make significant breakthroughs in deciphering Maya hieroglyphics. Repeating a trend started a century earlier with the mystical writing of Augustus Le Plongeon ('The Lure of Moo,' January/February 2007), pop-fringe literature such as Peter Tompkins's Secrets of the Mexican Pyramids, Frank Waters's Mexico Mystique, and Luis Arochi's The Pyramid of Kukulcan heralded secret knowledge of the future emerging from the Maya code. It was also about this time that promoting the idea of "shared beginnings," acquired by being at the right place at the right time, began to enter the tourism industry. Tourists, many with New Age spiritual leanings, flock to Chichén Itzá on the spring equinox, for example, to see a serpent effigy emerge in the shadows of El Castillo. Sacred tourism is already beginning to cash in on the 2012 myth. Star parties are planned for Copán and Tikal on the eve of the temporal turnover. And industrious entrepreneurs are already beginning to prepare 2012 survival kits, a Complete Idiot's Guide to 2012, and T-shirts bearing slogans such as "Doomsday 2012" and "Shift Happens." Not to mention the movie. This is just the beginning.

We live in a techno-immersed, materially oriented society that seems somewhat bewildered by where rational, empirical science might be taking us. This may be why the mystical, escapist explanations of a galactic endpoint, replete with precise mathematical, historical, and cosmic underpinnings (masquerading as science), have such wide appeal. In an age of anxiety we reach for the wisdom of ancestors--even other peoples' ancestors--that might have been lost in the drifting sands of time. Perhaps the only way we can take back control of our disordered world is to rediscover their lost knowledge and make use of it. And so we romanticize the ancient Maya.

But the glorious achievements of the Maya and other complex cultures of the ancient world are appealing enough on their own. We don't need to dress them up in Western or apocalyptic clothing. And the responsibility for educating the public about what we really know about the Maya and other extraordinary cultures--such as the ability of the Maya to follow the position of Venus to an accuracy of one day in 500 years with the naked eye--should fall squarely on the shoulders of those of us who spend our lives studying them. The Y12 hysteria could leave us asking whether we are doing our jobs, or whether the desire for cosmic connection and continuity is too strong for science and rationality to overcome.

Anthony Aveni is the Russell Colgate professor of astronomy and anthropology at Colgate University and author of the new book, The End of Time: The Maya Mystery of 2012.

Saturday, December 11, 2010

Snow covered StreetCar New Orleans

The photo above is from December 11, 2008. It's not mine. I grabbed off of a local site in 2008. I've enjoyed it as part of my screen saver display and decided that it would be a nice gift to share it with others.

The photo below is from a British site. It shows just how much snow fell. The snow didn't last long but it was fun while it did.

Now for a bit of New Orleans trivia:

The last time it had snowed in New Orleans was 2004, and we had Katrina the summer after. There was snow the winter before Besty in 1965. There are other snows before hurricanes. So many people were convinced that we were in for another big one in 2009. But what happened instead was, given hell had frozen over, the Saints won the Superbowl.

The city has only experienced measurable amounts of snow 17 times since 1850.

And for all those.... people... who think that this is proof that there is no "global warming"... remember global warming means the average tempurature of the whole globe is going up. What it means locally is climate change, not warmer every where.

Thursday, December 9, 2010

Meditation - be still and listen

This is a stresful time for many. Instead of slowing down and aligning with the seasons we speed up. I suggest that we all take some time and read the article below.

Meditation isn't just about relaxing

Meditation isn't just about relaxing

Tuesday, December 7, 2010

Loose the dark... loose the magic... loose the connection to the wider universe

International Dark-Sky Association works to encourage changes in our lifestyles that allow for dark starry nights. Below are just a few offerings from their latest newsletter.

A Stolen Sky

Avoiding Depression: Sleeping in Dark Room May Help

The fat cat cometh

Light at Night and Breast Cancer Risk Worldwide

A Stolen Sky

Avoiding Depression: Sleeping in Dark Room May Help

The fat cat cometh

Light at Night and Breast Cancer Risk Worldwide

Wednesday, November 10, 2010

New Orleans Fringe Festival

When does the edge move to the center? This looks like the year for the New Orleans Fringe Festival as it unveils more than 150 shows from 60 performing groups during its run from Nov. 17 to 21.

The 2010 New Orleans Fringe Festival runs from Nov. 17 to 21 with performances scheduled throughout the city.

One measure of the festival's growing importance is that international artists are traveling here for the first time, including some from as far away as Chile, Switzerland, Italy, Northern Ireland and Norway. The foreign contingent joins artists from across the United States for five days of drama, comedy, musical theater, cabaret, multimedia, dance, circus, sideshow and puppetry. The Fringe even sponsors a parade on St. Claude Avenue, which mixes festival performers and neighborhood folks. The Good Children Fringe Parade starts at St. Claude and Poland Avenues on Nov. 20 at 2 p.m.

Although most of the festival centers on a half-dozen locations in the downtown neighborhoods of Bywater and Marigny, the venues also include such -- dare we say "establishment" -- theaters as Le Chat Noir cabaret and Southern Rep. Other venues are as alternative as the performers. This year, for example, shows will be staged in the Den of Muses, an industrial building in Marigny that house floats for the Krewe du Vieux.

Another first for the festival will be a weekend of free daytime children's activities, such as improv workshops, double-dutch contests and art-making activities. They will take place in the Free-For-All tent -- in Plessy Park at Royal and Press streets, beside the festival's central box office. It's a good place to put up your feet, sip a beer, grab a snack or shop the Fringe Market for crafts.

For tickets and details about all the shows, visit nofringe.org.

Southern Rep is currently featuring "Afterlife: A Ghost Story" by Steve Yockey. It's the world premiere of a piece that will go on to theaters in Boston and Los Angeles with support from the National New Play Network. Set in a beach house with a storm approaching, this hair-raiser follows a grieving couple through a plot full of sudden twists and surprises. Southern Rep artistic director Aimee Hayes staged "Afterlife, " with an all-star local cast: Lucy Faust, Michael Aaron Santos, John Neisler, Troi Bechet, Lisa Picone and Andrew Farrier. It runs through Nov. 7. Call 504.522.6545 or go to SouthernRep.com.

Cripple Creek Theatre Company does its part to promote new plays by presenting a trilogy of one-acts in November. Written by the troupe's artistic director, Andrew Vaught, "A Crude Trilogy" is directed by Emilie Whelan. She recently staged a sell-out production of "The Madwoman of Chaillot" for this spunky downtown company. "Crude" opens on Nov. 5 and runs on weekends through Nov. 13. Call 504.891.6815 or go to cripplecreekplayers.org.

Anthony Bean Community Theater continues its run of "Ceremonies in Dark Old Men" by Lonnie Elder III. Set in a rundown Harlem barbershop, this 1969 stage classic centers on the struggles of an aging patriarch and his fractured family. For the New Orleans production, which closes on Oct. 31, Anthony Bean directs a cast of seven, including such notable actors as Harold X. Evans and Damany S. Cormier. Call, 504.862.7529 or go to anthonybeantheater.com.

Saints fans have a chance to celebrate at the theater this month with two notable local shows. "Ain't Dat Super" debuted at the Mahalia Jackson Theatre for the Performing Arts over the Labor Day weekend. It will return to the big hall in Armstrong Park on Nov. 13. Set in a New Orleans bar, the show features beloved local actors -- Becky Allen and John "Spud" McConnell -- in a comedy loaded with Saints trivia. There is even a chance to "tailgate" before the curtain rises. Call 888.946.4839 or go to aintdatsuper.com.

There's also time to catch the final show of "Bless Ya Boys: Who Dat Nation" at Le Chat Noir cabaret on Thursday. It's the fourth year for this popular seasonal review which looks back, with a smile, at 40 years of Saints history. Other shows at the Le Chat include a pair of comedies "Good Night and the Island of Dr. Fitzmorris!" Friday and Saturday and "Love Child" (opens with a benefit show on Nov. 4 and continues on weekends through Nov. 21). Call 504.581.5812 or go to cabaretlechatnoir.com.

Le Petit Theatre also focuses on laughs with "Forbidden Broadway, " which runs at the French Quarter venue Nov. 5 through 19. The comedy spoofs familiar stage actors and Broadway shows. It has evolved in the decades since winning a 1981 Tony Award in New York. It now includes send ups of "Hairspray" and other more recent work. Call 504.522.2081 or go to lepetittheatre.org.

The 2010 New Orleans Fringe Festival runs from Nov. 17 to 21 with performances scheduled throughout the city.

One measure of the festival's growing importance is that international artists are traveling here for the first time, including some from as far away as Chile, Switzerland, Italy, Northern Ireland and Norway. The foreign contingent joins artists from across the United States for five days of drama, comedy, musical theater, cabaret, multimedia, dance, circus, sideshow and puppetry. The Fringe even sponsors a parade on St. Claude Avenue, which mixes festival performers and neighborhood folks. The Good Children Fringe Parade starts at St. Claude and Poland Avenues on Nov. 20 at 2 p.m.

Although most of the festival centers on a half-dozen locations in the downtown neighborhoods of Bywater and Marigny, the venues also include such -- dare we say "establishment" -- theaters as Le Chat Noir cabaret and Southern Rep. Other venues are as alternative as the performers. This year, for example, shows will be staged in the Den of Muses, an industrial building in Marigny that house floats for the Krewe du Vieux.

Another first for the festival will be a weekend of free daytime children's activities, such as improv workshops, double-dutch contests and art-making activities. They will take place in the Free-For-All tent -- in Plessy Park at Royal and Press streets, beside the festival's central box office. It's a good place to put up your feet, sip a beer, grab a snack or shop the Fringe Market for crafts.

For tickets and details about all the shows, visit nofringe.org.

Southern Rep is currently featuring "Afterlife: A Ghost Story" by Steve Yockey. It's the world premiere of a piece that will go on to theaters in Boston and Los Angeles with support from the National New Play Network. Set in a beach house with a storm approaching, this hair-raiser follows a grieving couple through a plot full of sudden twists and surprises. Southern Rep artistic director Aimee Hayes staged "Afterlife, " with an all-star local cast: Lucy Faust, Michael Aaron Santos, John Neisler, Troi Bechet, Lisa Picone and Andrew Farrier. It runs through Nov. 7. Call 504.522.6545 or go to SouthernRep.com.

Cripple Creek Theatre Company does its part to promote new plays by presenting a trilogy of one-acts in November. Written by the troupe's artistic director, Andrew Vaught, "A Crude Trilogy" is directed by Emilie Whelan. She recently staged a sell-out production of "The Madwoman of Chaillot" for this spunky downtown company. "Crude" opens on Nov. 5 and runs on weekends through Nov. 13. Call 504.891.6815 or go to cripplecreekplayers.org.

Anthony Bean Community Theater continues its run of "Ceremonies in Dark Old Men" by Lonnie Elder III. Set in a rundown Harlem barbershop, this 1969 stage classic centers on the struggles of an aging patriarch and his fractured family. For the New Orleans production, which closes on Oct. 31, Anthony Bean directs a cast of seven, including such notable actors as Harold X. Evans and Damany S. Cormier. Call, 504.862.7529 or go to anthonybeantheater.com.

Saints fans have a chance to celebrate at the theater this month with two notable local shows. "Ain't Dat Super" debuted at the Mahalia Jackson Theatre for the Performing Arts over the Labor Day weekend. It will return to the big hall in Armstrong Park on Nov. 13. Set in a New Orleans bar, the show features beloved local actors -- Becky Allen and John "Spud" McConnell -- in a comedy loaded with Saints trivia. There is even a chance to "tailgate" before the curtain rises. Call 888.946.4839 or go to aintdatsuper.com.

There's also time to catch the final show of "Bless Ya Boys: Who Dat Nation" at Le Chat Noir cabaret on Thursday. It's the fourth year for this popular seasonal review which looks back, with a smile, at 40 years of Saints history. Other shows at the Le Chat include a pair of comedies "Good Night and the Island of Dr. Fitzmorris!" Friday and Saturday and "Love Child" (opens with a benefit show on Nov. 4 and continues on weekends through Nov. 21). Call 504.581.5812 or go to cabaretlechatnoir.com.

Le Petit Theatre also focuses on laughs with "Forbidden Broadway, " which runs at the French Quarter venue Nov. 5 through 19. The comedy spoofs familiar stage actors and Broadway shows. It has evolved in the decades since winning a 1981 Tony Award in New York. It now includes send ups of "Hairspray" and other more recent work. Call 504.522.2081 or go to lepetittheatre.org.

Monday, November 1, 2010

Shadowfest Cemetary Visit

Saturday, October 30, 2010

Now that's Scary!!!!!

Friday, October 22, 2010

Charge of Aradia

Whenever you have need of anything, once in the month when the Moon is full, then shall you come together at some deserted place, or where there are woods, and give worship to She who is Queen of all Witches. Come all together inside a circle, and secrets that are yet unknown shall be revealed.

And your mind must be free and also your spirit, and as a sign that you are truly free, you shall be naked in your rites. And you shall rejoice, and sing; making music and love. For this is the essence of spirit, and the knowledge of joy.

Be true to your own beliefs, and keep to the Ways, beyond all obstacles. For ours is the key to the mysteries and the cycle of rebirth, which opens the way to the Womb of Enlightenment.

I am the spirit of witches all, and this is joy and peace and harmony. In life does the Queen of all witches reveal the knowledge of Spirit. And from death does the Queen deliver you to peace and renewal.

When I shall have departed from this world, in memory of me make cakes of grain, wine and honey. These shall you shape like the Moon, and then partake of wine and cakes, all in my memory. For I have been sent to you by the Spirits of Old, and I have come that you might be delivered from all slavery. I am the daughter of the Sun and Moon, and even though I have been born into this world, my Race is of the Stars.

Give offerings all to She who is our Mother. For She is the beauty of the Greenwood, and the light of the Moon among the Stars, and the mystery which gives life, and always calls us to come together in Her name. Let Her worship be the ways within your heart, for all acts of love and pleasure gain favour with the Goddess.

But to all who seek Her, know that your seeking and desire will reward you not, until you realize the secret. Because if that which you seek is not found within your inner self, you will never find it from without. For she has been with you since you entered into the ways, and she is that which awaits at your journey's end.

And your mind must be free and also your spirit, and as a sign that you are truly free, you shall be naked in your rites. And you shall rejoice, and sing; making music and love. For this is the essence of spirit, and the knowledge of joy.

Be true to your own beliefs, and keep to the Ways, beyond all obstacles. For ours is the key to the mysteries and the cycle of rebirth, which opens the way to the Womb of Enlightenment.